Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia seen in clinical practice. It is a perennial hot topic for General Practitioners and remains a very common source of MRCGP exam questions. The diagnosis and management of AF presents some serious challenges, and there have been several significant new developments over recent years. It remains an important contributor to population morbidity and mortality, being particularly common in the elderly, and growing in prevalence with the ageing of the population.

AF can be defined as an abnormal heart rhythm that is characterised by the rapid and irregular beating of the atria. This results in an irregular and often abnormally fast heart rate. Physiologically there is a loss of active ventricular filling, which is associated with:

- Stagnation of blood in the atria, leading to thrombus formation, and a risk of embolism, which in turn can cause stroke

- Reduction in cardiac output, which can result in the development of heart failure

There are currently two sets of guidelines that are commonly quoted and used in UK practice, the 2021 NICE guidelines, and the 2016 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines. We recommend that, at present, MRCGP candidates are familiar with both sets of guidelines and key learning points from both are discussed in the notes below.

Important terminology

In order to fully understand the management of AF, it is important to have a good understanding of the terminology used to describe the different subtypes that can occur.

|

Causes of atrial fibrillation

A wide range of medical conditions can cause AF, and these are commonly grouped into cardiac and non-cardiac causes:

|

Lone AF is defined as AF without overt structural heart disease and characterised by a normal clinical history and examination, ECG, chest X-ray and, more recently, the echocardiogram.

Investigating atrial fibrillation

Baseline blood tests should be arranged for all patients, to assist in the recognition of an underlying condition and risk stratification. These should include:

- Full blood count

- Renal function and electrolytes

- Thyroid function tests

- Liver function tests

- Coagulation screen

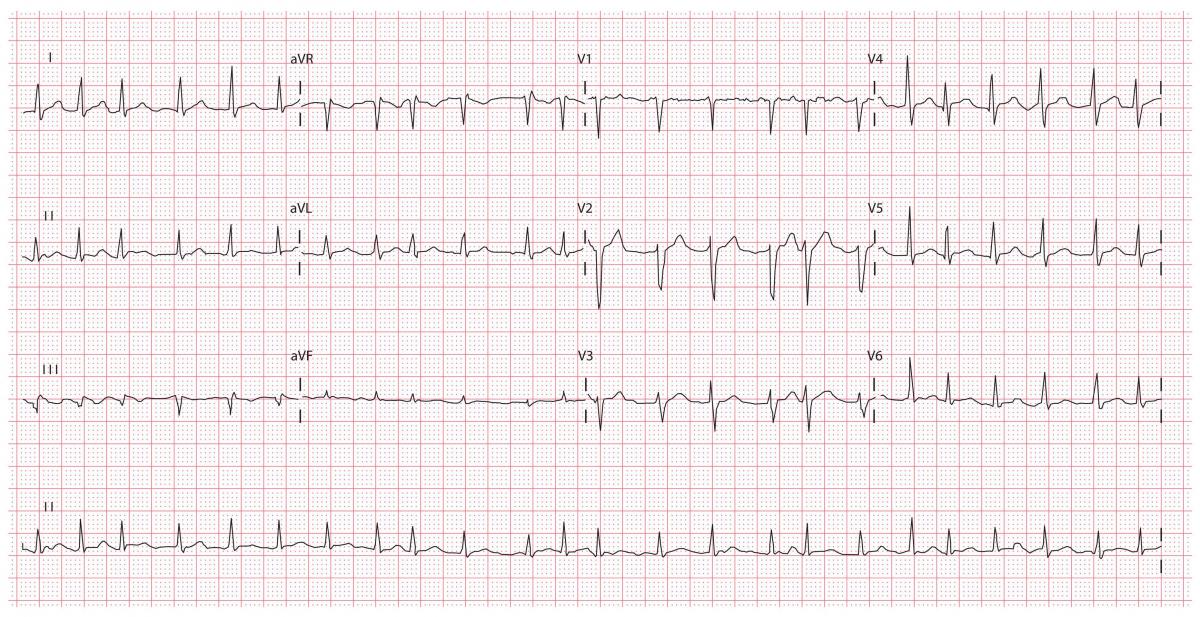

It is recommended that an ECG is performed in all patients with suspected AF, regardless of whether or not they are symptomatic. This would generally be following the detection of an irregular pulse.

The classic ECG features of AF are:

- Irregularly irregular rhythm

- Absent p waves

- Irregular ventricular rate

- Presence of fibrillation waves

ECG example of AF with a rapid ventricular rate

ECG example of AF with a rapid ventricular rate

It is important to remember that an ECG is only diagnostic in non-paroxysmal attacks. If paroxysmal AF is suspected and has not been detected by a standard ECG recording, a 24-hour ambulatory ECG monitor should also be organised. If reported episodes are more than 24 hours apart, then an event recorder ECG is indicated.

The guidance on whether or not transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is indicated differs between the NICE 2021 and the ESC 2016 guidelines:

- NICE 2021 – TTE is only recommended if it is likely to change management and should be guided by the clinical judgement of the referring clinician (e.g. when considering a rhythm control strategy or when there is a high risk of underlying or structural heart disease)

- ESC 2016 – TTE is recommended for ALL patients

Managing atrial fibrillation

The management of AF involves the control of the arrhythmia (by either rhythm or rate control) and thromboprophylaxis for stroke prevention.

Any underlying cause should also be treated, e.g. pneumonia or thyrotoxicosis, and any co-existing heart failure should be treated appropriately.

Indications for referral

Urgent referral for admission to hospital is indicated when:

- There is a very rapid pulse (greater than 150 bpm) and/or low BP (systolic BP <90 mm Hg)

- There is loss of consciousness, severe dizziness, ongoing chest pain, or increasing breathlessness

- There is a complication of AF (e.g. stroke, TIA or acute heart failure)

Routine referral to a cardiologist should be considered when:

- The person is young (e.g. <50 years of age)

- Paroxysmal AF is suspected

- There is uncertainty regarding whether rate or rhythm control should be used

- Drug treatments that can be used in primary care are contra-indicated or have failed to control symptoms

- The person is found to have valve disease or left ventricular systolic dysfunction on echocardiography

- Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome or a prolonged QT interval is suspected on the ECG

Rate or rhythm control?

There is currently no evidence that rhythm control is superior to rate control in preventing stroke or overall mortality in patients with AF. Therefore, rate control is the first-line strategy in the majority of patients.

Referral for a rhythm control strategy is indicated in patients with:

- New-onset AF

- AF with a reversible cause

- Patients with co-existing heart failure and AF

- Patients with atrial flutter

- AF that remains symptomatic despite good rate control

Rate control should be achieved as follows:

- A standard beta-blocker (not sotalol), e.g. atenolol or bisoprolol, or a rate-limiting calcium channel blocker, e.g. diltiazem, is the first-line therapy of choice

- Digoxin can be considered in patients who do no or little physical exercise or when other rate-limiting options are rules out because of co-morbidities or the person's preference

- If monotherapy does not control the patient's symptoms, and if continuing symptoms are thought to be caused by poor ventricular rate control, combination therapy should be considered with any two of the following: a beta-blocker, diltiazem and digoxin

- Amiodarone should NOT be offered for long-term rate control

Assessing stroke risk

The CHADS-VASc (or CHA2DS2-VASc) scoring system is an updated scoring version of the CHADS2 core used to assess stroke risk for patients with atrial fibrillation.

The CHA2DS2-VASc score is calculated as follows:

- C – Congestive heart failure (1 point)

- H – Hypertension (1 point)

- A2 – Age > 75 years (2 points)

- D – Diabetes mellitus (1 point)

- S2– Prior stroke or TIA (2 points)

- V – Vascular disease (1 point)

- A – Age 65-74 years (1 point)

- Sc – Sex category (female gender) (1 point)

If the score is 2 or greater the patient is high risk, and the patient should be anticoagulated with a direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC) if there are no contraindications.

Assessing bleeding risk

The 2021 NICE guidelines recommend using the ORBIT bleeding risk score to identify patients at high risk of bleeding. A review of the evidence has revealed that the ORBIT score is more accurate as a risk predictor than the previously used HAS-BLED score. The ORBIT score estimates the risk of major bleeding for patients in AF being considered for anticoagulation. It is often used in combination with the CHA2DS2-VASc score when making a decision on anticoagulation for these patients.

The components of the ORBIT score are as follows:

- Older – age >74 (1 point)

- Reduced haemoglobin or Bleeding history – Any history of GI bleeding, intracranial bleeding, or haemorrhagic stroke (2 points)

- Insufficent kidney function – GFR <60 mL/min/1.73m2 (1 point)

- Treatment with antiplatelet agents – (1 point)

A score of 0-2 is deemed low risk (2.4 bleeds per 100 patient-years), 3 is medium risk (4.7 bleeds per 100 patient-years), and 4-7 is high-risk (8.1 bleeds per 100 patient-years).

By comparison, the 2016 ESC guidelines do not advocate the use of this score to assess bleeding risk. Instead, they recommend that clinicians use clinical judgement and correct modifiable risk factors. The ESC 2016 guidelines list the following as modifiable risk factors:

- Hypertension (esp. systolic BP > 160 mmHg)

- Labile INR or time in therapeutic range (TTR) < 60% in patients on warfarin

- Medications predisposing to bleeding, e.g. NSAIDs, antiplatelets

- Excessive alcohol intake (>8 drinks per week)

Specialist advice should be sought for patients with non-modifiable risk factors for bleeding, e.g. active cancer, prior major bleed history etc. Both sets of guidance agree that falls are not a reason to withhold anticoagulation unless they are severe and uncontrolled.

Which anticoagulant should be used?

Both the 2021 NICE and the the 2016 ESC guidelines recommend the use of a direct-acting oral anticoagulant DOAC). A November 2017 Systematic review with network meta-analysis showed that DOACs as a class are more effective, safer and reduced all-cause mortality compared to warfarin. There is no current antidote for DOACs, but research has shown that they are still safer than warfarin, even without the potential for reversibility.

Apixaban 5 mg bd was ranked as the most effective DOAC for reducing stroke and all-cause mortality and was also the safest with the lowest incidence of bleeding. The bleeding risk is still significant though, at 1-2% annum.

DOACs are also cost-effective, and despite high drug costs, they are cost-effective overall due to the reduced risk of stroke and hospitalisation.

If direct‑acting oral anticoagulants are contraindicated, not tolerated or not suitable in people with atrial fibrillation, offer a vitamin K antagonist (e.g. warfarin). For adults with atrial fibrillation who are already taking a vitamin K antagonist and are stable, continue with their current medication and discuss the option of switching treatment at their next routine appointment, taking into account the person's time in therapeutic range.

What about patients that are already taking aspirin?

Around 15% of patients with atrial fibrillation also have co-existing coronary artery disease for which they are already prescribed aspirin or other antiplatelet medications. The combination of antiplatelet medications with anticoagulants significantly increases bleeding risk but also reduces the risk of vascular events. Aspirin monotherapy solely for stroke prevention in patients with AF should not be offered.

The 2016 ESC guidelines recommend that for patients that require anticoagulation for AF, co-prescription of antiplatelet medications should be avoided unless there is a clear indication for platelet inhibition. Their guidance is summarised below:

|

What is the prognosis for patients with AF?

Despite recent advances in the management of AF, there is still a reduced life expectancy for older patients. People with AF have double the mortality and a five-fold higher risk of stroke than those without fibrillation. Ultimately, the overall prognosis depends greatly on the patient’s underlying medical condition.

Further reading:

NICE 2021 guidelines on atrial fibrillation

European Society of Cardiology (ESC) 2016 guidelines